If you have a Netflix subscription you might have come across Toxic Town, the story of how the contaminated soil from a decommissioned steelworks in the UK led to many cases of developmental abnormalities and the birth of children with affected limbs during the 1990s. The drama focused on the efforts of a dedicated solicitor to expose the lies and deception of those involved, particularly the local council, and told the tale of some of the families most affected. It is not easy to watch, whatever your connection to the story.

For me, it was a story I already knew well, because I grew up in Corby, the town affected, and lived there from 1965 when I was four until I left for university in 1979. While I was at university the steelworks was closed down in the service of a cruel ideology that measured value only in terms of profit, and my mum moved back to the North East, so I never went back to live there after I graduated.

So I wasn’t in Corby when the lorries loaded with toxic topsoil drove through town to the dump, and my children were neither conceived nor born in a house contaminated with heavy metals and the rest of the product of decades of iron and steel production at the works that dominated the town.

But those affected were my contemporaries or near contemporaries, and anyone represented in the programme who spoke with a Glaswegian accent would have grown up in the same streets I did, shopped on Corporation Street and in Queen’s Square, use the swimming pool and boating lake, drunk in the White Hart and the Nag’s Head and (on a bad day) The Corinthian, and taken the bus to Kettering to catch a train to London or Scotland.

I didn’t expect the dramatisation to affect me, but when I came home last night and my wife was watching the end of the final episode I sat listening to the last ten minutes and it opened me up to a wave of grief and anger that I’m still not sure how to deal with. Not content with destroying the town at the end of the 80s the people who claimed to be helping, in the name of regeneration, permanently damaged another generation, and nobody was held to account because the only legal sanction was a civil suit and the payment of damages.

The people responsible for the closure – like Thatcher and Ian MacGregor, the head of the British Steel Corporation who closed the steelworks – walked away, like the guilty do so often in our country where justice is so unevenly distributed, and that feels lke a separate form of trauma for those who suffered so much. And those who allowed the toxic waste to spread through the town were similarly insulated from real accountability.

I was born in Newcastle and lived in Jarrow until the family moved South to Corby, and I’ve written before about what it feels like when your heritage is dominated by the careless destruction of industrial towns in pursuit of ideology and profit

Living in Corby

Corby doesn’t appear that often in stories, but I reread John Burnside’s Living Nowhere recently, set in the town in the 70’s and 80’s and featuring the Corinthian pub and many other places I knew so well that reading it took me vividly back to those times.

Burnside moved to Corby with his family from Scotland, as the steelworks brought so many people to the New Town with guaranteed work and good council housing. We were the same. It was also home to those fleeing for more than just economic reasons, like my friends Martin from Latvia or Milorad from Yugoslavia, whose parents were political refugees.

One of the most important spaces for me was the library, on George Street. I wrote about it for a book Blast Theory commissioned called A Place Free of Judgment, published in 2017:

I grew up in a town called Corby in Northants in the 1960’s, in a council house on a ‘rough’ estate. Corby Library was my gateway to a world that I could not have imagined otherwise, a space where I was both safe and nurtured, where the librarians encouraged my exploration and imagination, and pointed out a path that I would never have discovered otherwise. I read the books. All the books. Any of the books. And when I discovered the science fiction section, I discovered a multitude of universes to explore. I also remember being allowed to borrow The Godfather by Mario Puzo, before I was old enough to see the film, and realising that the whole world lay before me.

And there was more: at the back of the reference section was a secret portal – a door to the library of the Technical College, located next door. I remember passing through it for the first time, the engineering and science books it contained, the world it hinted at. I look back now and I realise that one of the reasons why I believed enough in myself to apply for and successfully get to university – the only person in the sixth form of my comprehensive school to manage it – was because the library was my runway, and I’d built up enough momentum in my time there to become airborne.

The library burned down in the late 70’s. I’d left. I didn’t go back.

In fact I did go back, to visit if not to live, and I think the time has come to find my way back there more regularly. Over the last fifteen years or so I’ve recovered my connection to the North East, initially through my work with Tyneside Cinema as part of their centenary and then with the BBC where I’ve helped to build a technology team in the North East, based in the BBC offices on Barrack Road. I’ve talked about my past, and the sense of being a Geordie.

But I’ve been less aware of and engaged in the story of Corby, even though I feature on the Wikipedia page for ‘People from Corby’. I think it’s because I left, and distanced myself from the town during the hard years of the 1980’s as I established my life in Cambridge. It wasn’t my decision to leave the North East, so going back on my own terms felt acceptable, felt like something that might be permitted, but I had left Corby behind.

I think I was wrong, that Corby made me as much as Jarrow did, and that putting it to one side means I’ve failed to think about things that are important to who I am, how I see the world, and Toxic Town has only reinforced my sense of connection to the space of my childhood.

Other Writing

I wrote about what other people thought of Corby, in 2006

I wrote about the transition from Corby to Cambridge on my 40th anniversary in 2019

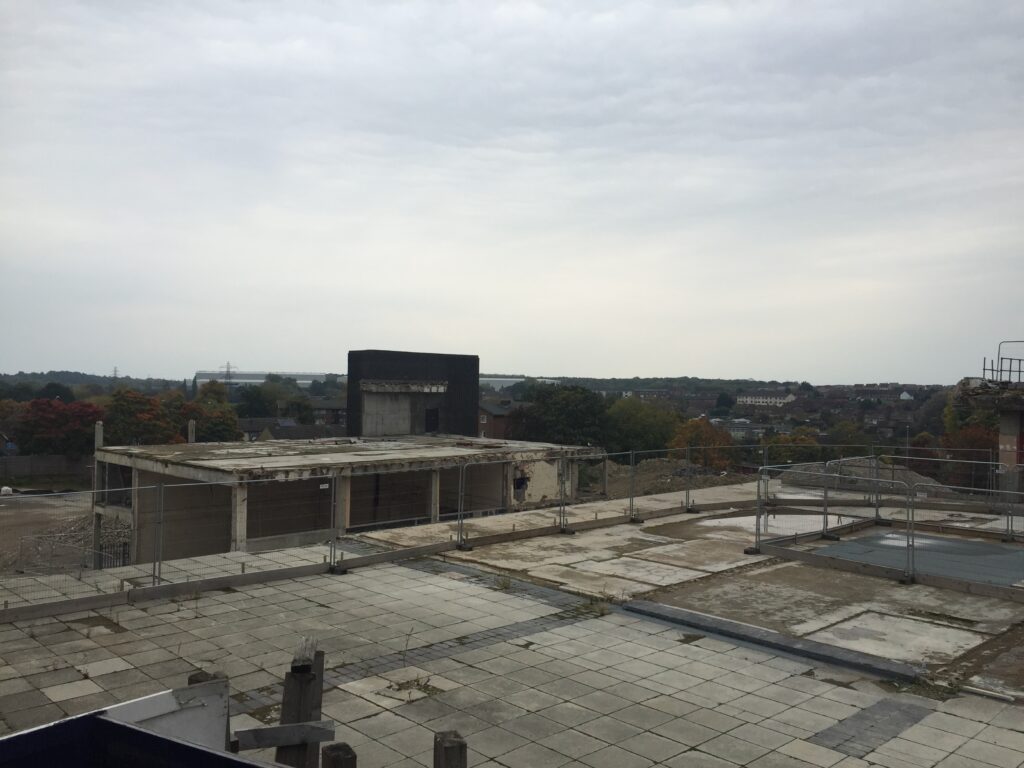

They tore down Queen’s Square a few years ago