Paying off our ecological debt

StandardIt’s usually dangerous to draw analogies between computing and any other field except possibly mathematics, because the way we do things in computing is so bounded by technical constraints, business models, and naive modelling assumptions that trying to apply our approach in other domains is either laughably simplistic or clearly unhelpful.

However as I reflect on the state of the world as the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic continues to disrupt so much about the lives of so many, it seems that one idea from our profession offers a useful way of thinking about what we are going through.

That idea is ‘technical debt’: the cumulative impact of taking the easy path to delivering a solution instead of doing it properly that will one day be repaid, either by redoing the work as bug reports come through, or through lost data, lost effort and lost trust in the software.

The Day William Gibson Wrote Me a Suitcase in Cyberspace

StandardAlthough he came up with the term ‘cyberspace’ in the early 1980’s, William Gibson entered a version of it for the first time on October 9, 1999, in a darkened room in Cheltenham Town Hall during the town’s literary festival. I know, because I was his guide and he told me so.

We had just come off the main stage after a discussion about his recently published novel ‘All Tomorrow’s Parties’, and I’d invited him to the festival’s online zone to hang out with me in LinguaMOO, a text-only teaching system where I had a virtual office.

After he’d signed some books we went into the computer room and he logged in as Bill_Gibson, chatting for a few minutes with members of the the LinguaMOO community, including the TrAce writing community that I was part of. He started off well:

Bill_Gibson says, “Hello, this really is Wm. Gibson, tho you won’t believe me…”

The Messy Edge of the Liminal Space

StandardThese are my notes for a talk I gave at the Messy Edge, a conference curated by Laurence Hill as part of Brighton Digital Festival 2019, at the University of Sussex on October 18 2019.

When My World Changed: Forty Years of Cambridge

StandardI had just turned 19 when arrived in Cambridge in October 1979, with a full grant and a maintenance payment which meant it didn’t cost me or my parents anything.

I’d been brought up by my mum in a council house on one of the tougher council estates in Corby, Northants, and we weren’t in a position to pay fees or well-disposed to taking out loans and if it hadn’t been for the implementation of the Robbins Report I doubt I’d have gone to any university.

Find out about the Robbins Report

Corby was a thriving new town with a massive steelworks when we moved there in 1965, moving down from Tyneside with my mum and sister. One of my earliest memories is arriving in Brixham Walk, parking near a lamppost and walking from the road to the house in the dark. We lived there for the next fourteen years.

Ten years at the BBC

StandardOn September 21 2009 I sat with Roly Keating, at the time the Director of Archive Content for the BBC, outside this Starbucks in what was the BBC’s Media Centre, and talked to him about taking on a six month role to work in his team as the Head of Partnership Development. It was a quick job, sorting out a partnership strategy for the recently formed BBC Archive Development team run by Tony Ageh and setting up a couple of key agreements.

I’d been asked to go for the job by Tony as he and I had worked together back in 1994 when he ran The Guardian’s innovation group, the PDU, and I’d come over from PIPEX to run the New Media Lab and build the first iteration of The Guardian’s online presence. We’d stayed in touch since, and I’d been involved after he had arrived at the BBC in 2001. After working to develop the website and iPlayer, Tony was currently trying to make the archive more accessible, especially to other cultural institutions.

Complicity

StandardOver the last few weeks the degree of complicity between the technology community and the financier Jeffrey Epstein has started to become apparent, and it makes difficult reading for all of us in that community, because it shows that many of the people we believed were sincere in their attempts to develop technologies that could sustain humanity were happy to have a convicted paedophile in their midst and listen to his ill-formed ideas, take his money, burnish his reputation and even lie about his involvement in their work.

It’s hard to believe we’re all working to enhance the human condition when that’s the case, and the awareness of our involvement should be the occasion for some serious reflection and changes to our assumptions and behaviour.

My awareness of Epstein came from news coverage of his crime, especially the reporting of Julie Brown in the Miami Herald. He appeared to be another man who used his power – in his case derived from wealth rather than celebrity – to exploit and abuse children, another predator whose behaviour was odious and yet tolerated by those around him, and who used his influence to gain immunity.

Julie Brown: https://www.miamiherald.com/news/local/article220097825.html

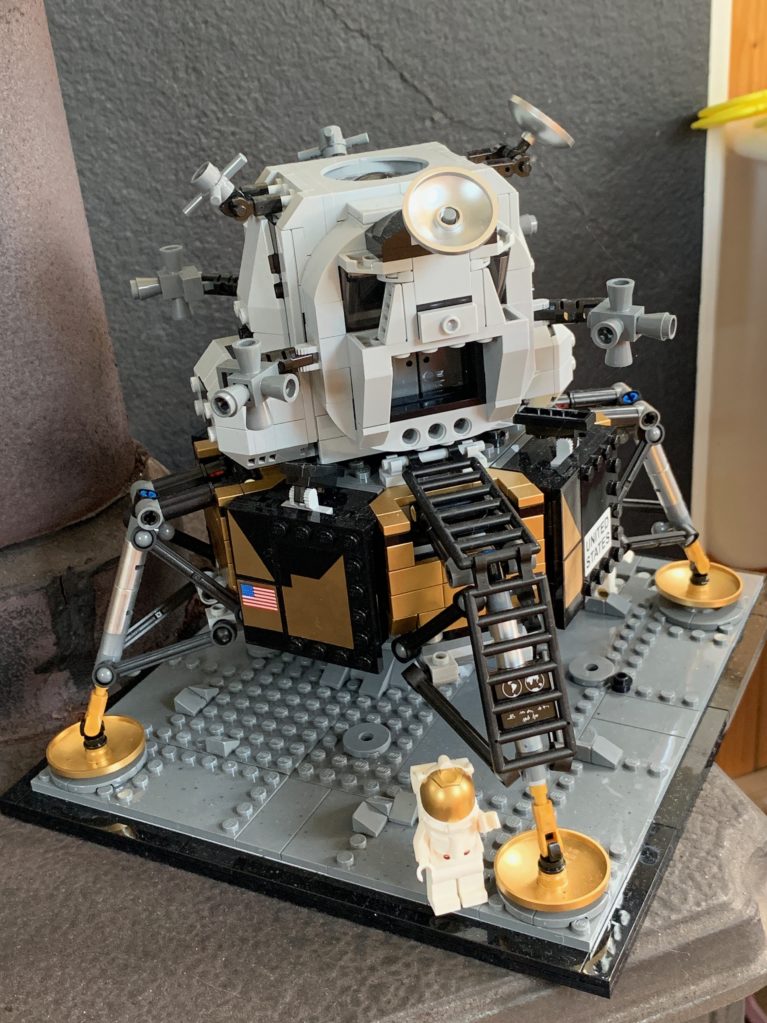

Learning from Apollo

StandardApollo 11 is more than nostalgia for me, it’s a way to think about tomorrow’s challenges

If you’re interested in the fiftieth anniversary of the Apollo 11 lunar mission then you’re probably already completely entranced by the BBC World Service podcast 13 Minutes to the Moon, in which Kevin Fong dissects the landing and puts every aspect into a broader technical, political, social and profoundly human context.

It’s an outstanding series in every respect, combining archive footage from the mission and old and new interviews with many of those involved, with an intelligent script and beautiful sound design, and I can’t recommend it enough. Produced by Andrew Luck-Baker and with Rami Tzabar as Executive Producer, it’s brilliantly made and one of the best audio documentaries you can find online.

If you work in computing or engineering then it’s worth it just for the insight into the complexities of the hardware and software involved, as it doesn’t hold back from going into technical details about the engineering and coding challenges, giving you all the background you need to be fully present as the lunar excursion module separates from the command module and begins to descend. Knowing how it ends doesn’t diminish the power of the story, or the emotional investment you make as a listener.

It’s worth listening to every episode – each is around 45 minutes – but if you don’t have time the whole thing then I urge you to listen to Episodes 8 and 9, which take you from the separation of the two spacecraft in lunar orbit – the Command Module and the Lunar Excursion Module – to the final ’stay’ decision after landing. And that detail is what makes it so good – it doesn’t stop at the moment of touchdown, but covers the three points in the next two hours when Mission Control had to decide to stay or go. They stay.

The Day the Music Dies

StandardA long long time ago…

I was at the Janelle Monáe gig at Wembley Arena on Tuesday, and it was as magnificent as you’d expect from this brilliant performer. We stood close enough to see properly, and far enough back to dance properly.

Between songs she said something that resonated with me, and it has prompted me to finish a piece I’d been noodling around with for some weeks. Speaking with some emotion, she said that the reason she performed was to create memories, to pass something to each of us in the audience, and she expressed a hope that we’d pass the memories we were making tonight on to others.

In one way this echoes the grand concept of her songs, which reflect the world of an android named Cindi Mayweather, an alter-ego through whom Monáe explores ideas of technology and otherness. After all, the memories of androids can be stored and transferred – or wiped as in the Dirty Computer Emotion Picture [see https://www.jmonae.com/] that accompanies the album which links the songs together with a story in which defective androids – ‘dirty’ computers – have their memories erased to make them ’normal’.

But for me, as I looked around an auditorium filled with points of light from thousands of mobile phones – twenty years ago it would have been cigarette lighters but few people carry them any more and there are probably sprinklers in the roof now- it made me think of the real organic memories that were being made in this place, at this time, with these people, making this music. Memories that can’t be downloaded or moved around on the quantum equivalent of USB sticks. It made me wonder what happens to Janelle Monáe’s music when the last person in this room, the last person to have been in the same space as her as she performs, dies.

I’ve been thinking about this for a while, mostly because of Chopin and Buddy Holly, and because it’s forty years since I saw The Who play at Wembley, without Keith Moon.

First they came for the numberplates

StandardI don’t like being watched, especially when I don’t know who the watchers are, and the rapid growth in cameras in streets, shops, trains, buses, public spaces and private buildings has troubled me for many years.

Until recently the watchers were, at least, human – delightfully limited in their perceptual capacity and ability to identify or discriminate, tired and distracted and even bored with their job as they sat behind banks of monitors.

And of course most of the material was never even watched, instead being held on a hard drive on a neglected server in a dank office awaiting some incident that would require it to be reviewed, but more likely to be overwritten to make disk space for today’s similarly neglected footage.

This is no longer the case. More and more of the cameras that capture us as we go about our lives – like the one in this rail carriage watching me as I write – are not intended for human viewing at all, but are input sensors for an increasingly sophisticated surveillance machine. It used to be misleading to say that a camera was ‘watching’ you as it was just an image capture device – at some point a human being needed to do the actual watching.