This is the text I wrote in advance of my talk at Libraries Rewired on November 10 2023. I used it to develop slides, then spoke to the slides.

[Slide: tl;dr]

tl;dr

GenAI is about to do to libraries what Google did to GPs fifteen years ago, and you are not prepared.

[Slide: The Tempest]

Four hundred years ago the First Folio was published. The Tempest can teach us a lot.

Full AI-enabled the library lies

of its books are models made

those are prompts that were its staff

nothing of it that doth fade

but doth suffer an AI change

into something rich and strange,

Chainèd prompts ring its knell

ding-dong.

Hark! The model speaks, what will it tell?

After Wm Shakespeare.

About BT

[part II]

I’ve been thinking about thinking for a while. As a philosophy undergraduate I was interested in philosophy of mind, the question of what thinking and consciousness are. Then I did experimental psychology, exploring how the only type of minds we have easy access to work – ours. Then I did a masters in computing, and part of that was the quest to replicate the sort of capabilities of the human mind, and a search for human-level capability.

I first thought seriously about machines that might emulate human cognition in 1981, while looking at machine vision for a second year dissertation. My supervisor, a young post-doc, was Geoffrey Hinton.

Today I’m one of the group of people inside the BBC grappling with the implications of generative AI.

In between I was one of the early adopters and advocates for both the internet and the web, and bear my responsibility for not taking seriously the need to build safeguarding into these technologies from the very start.

So let’s consider what we mean when we say AI, how we might learn from our past mistakes, and what all this could mean for you all as libraries and information scientists.

About AI

[Slide: what is AI?]

I use the term AI to mean any one of the range of technologies, tools, theories, or models that fall under the OECD definition of an ‘artificial intelligence system’ (OECD, 2019):

“a machine-based system that is capable of influencing the environment by producing an output (predictions, recommendations or decisions) for a given set of objectives. It uses machine and/or human-based data and inputs to (i) perceive real and/or virtual environments; (ii) abstract these perceptions into models through analysis in an automated manner (e.g., with machine learning), or manually; and (iii) use model inference to formulate options for outcomes. AI systems are designed to operate with varying levels of autonomy1”.

‘Machine learning’ or ML is a subset of AI in which the performance of the system changes based on prior activity.

‘Discriminative AI’ describes a class of artificial intelligence techniques that generally focus on the task of classification or prediction by learning boundaries of classification between sets of data points.

‘Generative AI’ is a class of machine learning models capable of generating text, audio, or images using a natural language (or in some cases, a multi-modal) input prompt. =

I try not to use the term “artificial intelligence” any more, as it takes as uncontroversial a model of intelligence that is derived from race science and is closely linked to eugenics, and too often AI researchers act as if there is a unitary scale of ‘intelligence’ on which machines, and people, can be ranked.

In their book Artificial Intelligence Stuart Russell and Peter Norvig (Russell and Norvig, 2021) note that ‘”computational rationality” would have been a more precise and less threatening term to use in the 1950’s, but “AI” has stuck’.

Finally, I have to note that this talk about the future is given in the context of a climate emergency, and that there is a distinct possibility that we will fail to find a way forward that preserves the sort of civilisation that deploys advanced network computing infrastructure, or that has the capacity that to build and enjoy libraries.

But let’s embrace the doublethink and consider where we are and where we might go.

The AI Age

[Slide: computrainium]

AI can best be understood as a new set of capabilities being added to the computational infrastructure that sustains the modern world. Some of these capabilities may become available as new services, from new companies, but many of them will augment the current dominant platforms like Amazon Web Services, Google Cloud Platform, and Microsoft Azure. The platforms will seek to extract value from them as with existing services, and they will also offer new opportunities for innovation and market disruption.

Maybe we should think about it as ‘computrainium’ – the latest type of computronium, or a form of matter which supports computation

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Computronium

Most of the attention at the moment is on Generative AI, or GenAI. This is important and fast-moving is because it builds on the last thirty years of rapid development of the computers and networks that underpin the modern world.

[Slide: more than GenAI]

But while it may be the most significant wave of technical innovation this century2, it is not the totality of AI. If we treat AI as ‘the study and construction of agents that do the right thing’, where the right thing is the objective given to the agent (Russell and Norvig, 2021) then there are many areas of AI research, from robotics to rules-based systems, that are of equal importance, even if they do not receive such widespread attention.

And of course we already use AI in many different contexts, from recommendation systems to machine vision to image enhancement, network data analysis, and cyberthreat detection. These systems are transformative – for example they make machine pattern recognition straightforward, something that is not readily achievable using traditional software engineering approaches – even if they do not get the same attention as GenAI.

So, to begin.

[Slide: Turing paper]

In the era of ‘computrainium’ AI is not a separate thing, but another layer added to the computational infrastructure that runs the modern world. Not just generative AI but a whole range of software-defined capabilities that will approach or surpass human-level skills in a wide range of cognitive tasks. We are entering the era of machines that think, as predicted by Turing in 1950 in Computing Machinery and Intelligence, though a little late.

This is not about ‘artificial general intelligence’ or even about conscious/sentient machines – though I am starting to think that the latter may be coming soon, as a result of embedding chained LLMs into robots and therefore embodying their capabilities. It is about the impact of machines with genuine cognitive capabity on libraries, archives, information services, and their contents and – crucially – the professionals who animate them.

[Slide: framing the question]

Let’s put to one side the question of how much existing knowledge these machines will need access to in order to operate, and the rights issues that creates: these questions will resolve.

And let’s assume that there are forms of regulation around their development and use that enable their widespread adoption within acceptable parameters.

And let’s not worry too much about the existential risk that is used by many as a distraction from current harms.

[Slide: Caliban]

Because we’ve got more than enough to think about with issues of biased models, inaccurate outputs, excessive surveillance and unwanted deployment, environmental impact, the extractive nature of AI technologies, better-than-human capabilities in key areas of work, a fundamental challenge to education and assessment, and of course their impact on the work of information professionals including librarians and all the rest of you.

We have taught the machines how to think, and our profit on’t is they know how to hollow out the middle-class tax base by making many professional roles either redundant or more efficient – either way we need fewer people.

And since nobody is proposing to break the staff and abjure these rough models, we need to decide what we’re going to do.

[Slide: Prospero & Miranda]

The wider questions of the nature of the information ecosystem in an AI-fuelled age go deeper than did ever plummet sound.

[Slide: questions]

Here are some questions to consider:

What happens when search becomes rewriting?

Are voice interfaces going to be the norm?

Will chained LLMs be able to reason?

How dependent on the machines will we become for analysing large amounts of content/data?

What happens when the thinking machines are driving their own robots?

Are libraries equipped for this new set of resources to access and curate?

The information ecosystem, like many beaches, is being polluted. How do you operate in a dirty sea of disinformation?

Are AI outputs admissible in your collections?

What are the consequences of the great reindexing?

What will it be like to work with a competent AI assistant in ‘centaur’ mode?

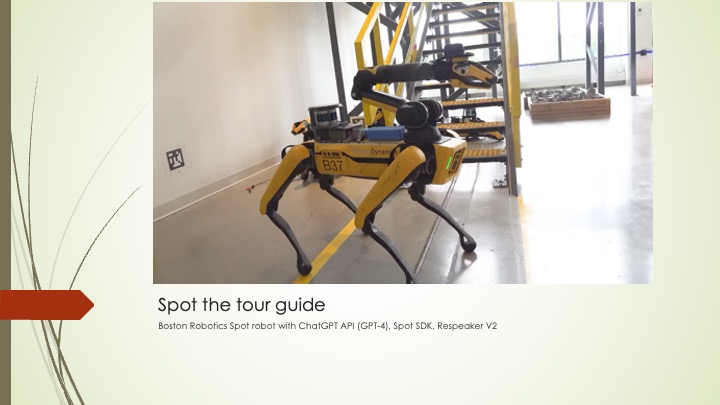

How are robots going to become useful – imagine asking Spot the Librarian to get a book from a shelf?

[Slide: Spot video https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=djzOBZUFzTw ]

And finally – what role might a library play when all the books have been ingested, but we’re still human beings.

Rates of Change

A building properly conceived is several layers of longevity of built components.”: Frank Duffy

[

Frank Duffy: rates of change

Site

Structure

Skin

Services

Spaces

Stuff

services, spaces and stuff are changing.. the skin will adapt – are we going to see new structures emerge? over what time frame, and how enduring?

Part of the problem is that we’re used to thinking about computing systems as moving the furniture around or, at most, knocking down a few walls. This time it’s different – we might be creating new buildings.

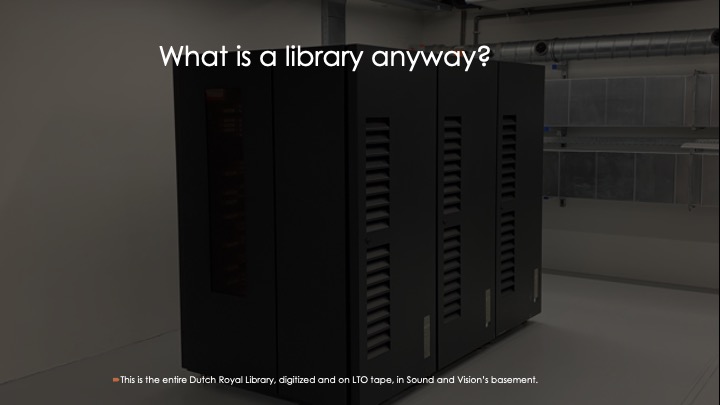

[slide: Royal Library of Netherlands on tape]

What matters in the library?

It might involve:

- being the most empathetic element in the loop

- having a human-shaped associative memory

- being able to read emotions in a voice or a face

- knowing what’s important and shaping the machine response towards it

- being fallible like an organic being

- but mostly, it will involve constantly making the argument for the thing libraries do, even though it’s rather hard to define.

Whateve the changes wrought by AI in the world, we need to hold on the the idea of the library is an expressed choice, a selection from the world, a series of decisions made manifest in the collection and the datasets and the catalogue.

A library does not make apologies for what is not there, it stands by what is.

Several ago I went to a reading by Don Paterson of some of the poems in Forty Sonnets on the top floor of Faber & Faber, introduced by Faber’s poetry editor Matthew Hollis. Before Don spoke, Matthew discussed what is was like to receive his manuscripts, to watch the poems as they were shaped, and he said something that has stuck with me since. He said ‘these words were DECIDED UPON’.

It’s true, and it matters,.

We need to decide not only what our libraries contain and what they offer but, in this time of enormous challenge, what we say when we say ‘library’. To decide that it means ‘something chosen’, in contrast to the great mass of everything on offer everywhere else.

So, can we capture the sense of the library and abstract something from it that will be worthy of the name in ten or twenty or fifty years time?

Well, the best way to predict the future is to create it.

Let’s build a future we’d like to live in, not inherit one from people who don’t understand the things we value.

[slide: Ned Ludd]

But perhaps this time a Luddite approach will work – solidarity in the face of the owners of capital whose spinning jennies are now LLM-enabled robots like Spot.

Let’s can start by engaging with the new capabilities on offer and decide how they work for you. Don’t let others decide what your future should be.

Let’s seize the means of computational rationality.