“As I write, highly civilized human beings are crafting algorithmic timelines, trying to kill my ability to focus for longer than thirty seconds.

“They do not feel any enmity against me as an individual, nor I against them. But their stock options and share prices depend on taking the most of my conscious attention as they possibly can.”

After Orwell, The Lion and the Unicorn

I had my first piece of writing for money published in 1979, a short essay in a book called The Condition of English Schooling edited by a friend of my then headmaster. It wasn’t very good, but they sent me a cheque anyway, and it means I’ve been a professional writer for over forty-five years now.

Being paid to think out loud is a privilege, and I’ve made my living doing it for newspapers and magazines and websites as a journalist, as well as writing papers and code and courses during my long career working in the tech industry.

If writing is one strand of my life, the Internet is the other, and they have always been entwined since the first time I encountered the network while doing the Diploma in Computer Science at Cambridge in 1984/5 and later when working for Acorn Computers from 1987. Acorn, as a partner in a university project, had access to the nascent Internet and we used it for email, moving files, and accessing the earliest social network, USENET.

There’s some background here: https://thebillblog.com/about-bill/new-media-dog/

Five years later I was working at PIPEX, the UK’s first commercial internet service provider, exploring the potential of the web and building websites for Anne Campbell MP, Comic Relief, and anyone else we could find who wanted to explore the new communications medium.

From there I went to the Guardian newspaper, developing their first online presence and website, and building the radically innovative five-language Eurosoccer.com for the 1996 Euro’96 football championships which – thirty years ago – had “continually up-dated match reports, features and comment from Europe’s top sports writers as well as live e-mail chats and profiles of all the players and teams throughout the championships. The site will also include a downloadable, updateable animated screensaver showing goals and highlights, on-line betting information and details on each of the host cities” in English, French, German, Italian and Spanish.

In those days I believed the net and the web would be a force for good, and held on to utopian visions of how society and the world would be improved by sharing and openness over an open, uncensored network. Tim Berners-Lee and I even agreed about this.

https://www.bbc.co.uk/blogs/digitalrevolution/2009/07/more-from-web-at-20.shtml

But in fact by the time I got to the BBC at the end of 2009, after thirteen years as a technology critic, commentator, advisor, consultant, and author, I was sceptical of the notion that an open, unrestricted network was a force for good and knew that I needed to atone for my earlier naivety. The BBC, I believed, was the machine through which we could redeem the network.

It was part of a wider change in my life. A couple of years earlier I’d met a great and radical activist, and in talking to her I realised that the impact I was having on the world as a lone operator wasn’t enough, that although people read and listened to me, it could never achieve change at scale. I decided to consider how I might do something more, and started looking at ‘real’ jobs

An opportunity to be creative director of a new interdisciplinary research unit at Cambridge University didn’t pan out when it failed to secure funding, but the process convinced me that I was ready for a bigger challenge than writing essays and giving talks.

At the same time the global financial meltdown had made the life of the free lance even more precarious, and the idea of getting regular salary every month became significantly more attractive.

And so when my old friend and colleague Tony Ageh (of the Guardian and iPlayer stories) called me up and asked if I’d be interested in a six month fixed term contract at the BBC helping sort out the BBC’s approach to partnerships for its archive I said yes. The money was good, I had done a lot of work with arts and cultural organisations, and even if it meant working inside a big organisation I could probably bear six months of tedious meetings. And if I was going to do anything to help rescue the internet and reshape the web, then the BBC was clearly a place to start. I had found my fulcrum, and the Archive Development team looked like a pretty good lever.

My appointment even made the papers: https://www.theguardian.com/media/pda/2009/nov/02/bbc-archive-bill-thompson, and I wrote about it a decade later:

The team in archive development reporting to Director Roly Keating was an interesting group, and we had an excellent time while it lasted. But first Roly left (for the BL) and then Tony left for the New York Public Library and took his job with him and we were left adrift in an organisation that lost any sense that the archive was more than a monetisable collection of clips or a load of old programmes that reminded people of why they loved the BBC.

This was a shame, as the ideas we developed between 2009 and 2012 were truly radical and still inform the wider public discourse about the impact of the internet on society and what a ‘better’ internet might look like.

We started from the premise that some way should be found to make the totality of the BBC’s archival collections, from programmes to photos to written documents to old scripts to orchestral scores, available to be seen, used and shared.

Just putting it all online wouldn’t work because the BBC didn’t actually own the rights to much of it, and because evidence showed that people would simply copy and (ab)use it. We wanted to have a controlled space where people around the world could engage with the memories the BBC had accumulated on their behalf, and a space within which the materials could be used within agreed limits. We were never going to get it all CC0 licensed (sorry, Andy, though we did try with some of it).

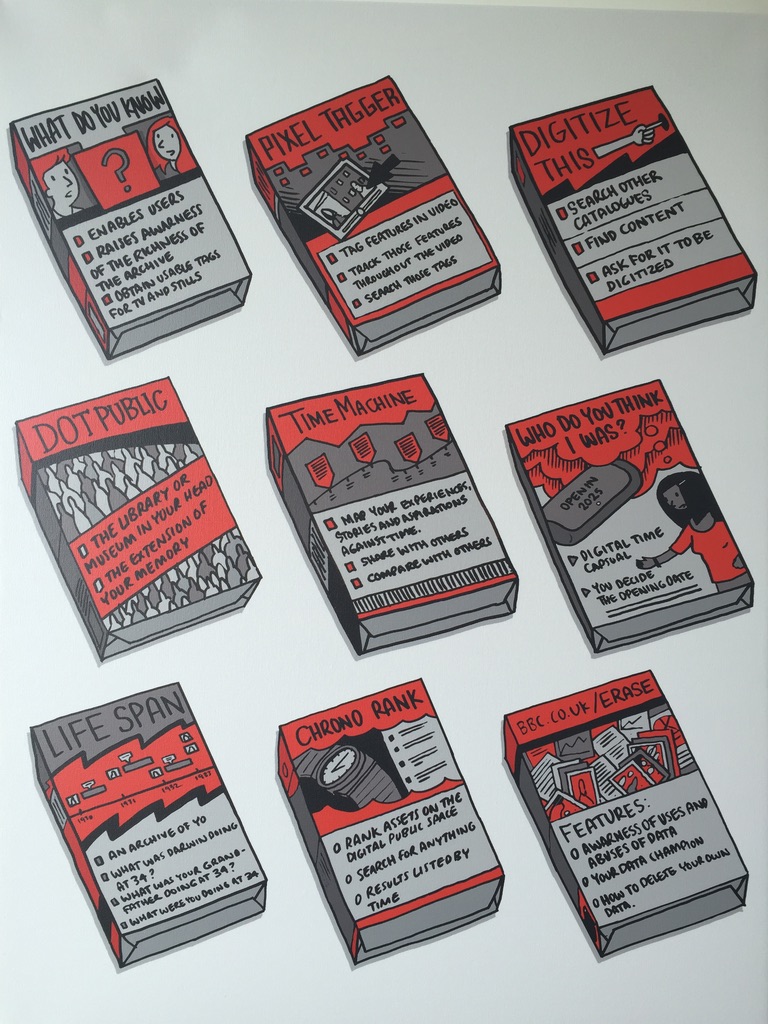

So we started thinking about ‘where’ it could all go, and developed the idea of a digital public space that could be a home for all sorts of material to be shared in the public interest.

There were lots of other initiatives around the same time, the most prominent being Europeana, a massive catalogue of Europe’s cultural assets. Europeana has an openly licensed catalogue and points to the assets themselves – mostly photographs of physical objects.

We were bolder, imagining an operating environment that would be somehow adjacent to the wider internet, offering users the choice of a safe, secure space within which they could access licensed material and use it within limits but with permission, and the ‘open’ internet of the west coast libertarians.

That thinking became the idea of the Digital Public Space

- See Baratsits paper: https://astickadogandaboxwithsomethinginit.com/thinking-about-the-digital-public-sphere/

- See CX pamphlet: https://futureeverything.org/news/digital-public-spaces/

- See JISC document: https://digitisation.jiscinvolve.org/wp/files/2014/12/141208-Towards-a-UK-Digital-Public-Space-A-Blueprint-Report-November-2014-WEB-VERSION.pdf ‘The core mission of a DPS proposed in this report is to open up public funded content for wider purposes and audiences’

One of the ‘pillars’ of the DPS was the idea that we could carve out a separate virtual network on top of the existing network infrastructure. In around 2011 this crystallised into the idea that we could have a special top level domain, .public or .public.uk, that would identify public service assets and that anything published in that space would have to come from an organisation that signed up to certain principles of good stewardship and good behaviour.

In a paper called “the Digital Public Space Initiative” we wrote:

“As we move into the digital age, the BBC is faced with new, unimagined challenges to its ability to ensure that its assets and services are universally available across multiple distribution platforms and devices. At the same time, a number of issues associated with the analogue era continue to apply, and place real limitations upon our ability to fulfil the Corporation’s primary obligation from the 1927 Charter: that the service “be developed and exploited to the best advantage and in the national interest”.”

And we suggested that a specialised top level domain was part of the answer:

“During the next year ICANN, the body responsible for managing online domain names, will accept applications for new generic top level domains. It may be that the BBC seeks to register .bbc. However we also propose to explore the possibility of securing a second domain, ‘.public’, on behalf of the BBC and other public bodies, opening up the possibility of creating domains such as bbc.public, bl.public and ace.public, to be created and managed just as bl.uk, bbc.co.uk and others are now.

“The dot public sites will initially be primed with archive based materials and cultural assets. Built in cooperation with other institutions, they will be available in the UK, and potentially globally. The use of this identifier allows institutions to clearly indicate that their online resources – whether audio/video assets, images, websites, programmes or databases – are indeed ‘public’ resources – in the same way as presence in their physical buildings make this clear in the physical world.

“Creating a clear and well-understood boundary between the public service and other online spheres of activity, will: clearly identify those assets and resources which are being offered in the public interest; reassure rights-holders, software developers and commercial users of the same technologies; manage any potential negative market impact of the DPS by providing mechanisms to keep material out of it where necessary.”

We went further, trying to figure out how you could use the domain as the anchor point for a technical architecture that would allow ‘zero rating’, so that access to the material within dot public would not count towards bandwidth caps. We even outlined how the BBC and other public organisations like museums, galleries and libraries could develop a public ‘freenet’ so that young people with limited data plans or people in poorer households could access government services and BBC iPlayer at no cost. It was tricky to reconcile with net neutrality – as Facebook found with Facebook Zero.

“Once established the .public domain could also be used to manage the delivery of online content over IP-based networks in a way that delivers the ‘free-to-air’ principle over the internet as it has been delivered via Freeview and Freesat for broadcast material.”

How Did it Go?

As you may have noticed, it didn’t happen. And since those relatively innocent days the open internet has become the toxic internet, and as you may also have noticed, we haven’t made any real progress on building a usable digital public space.

I haven’t given up on these ideas. I’m still at the BBC sixteen years later having spent six years in archive development, three on the Make it Digital digital literacy project and seven (and counting) on the leadership team in BBC Research & Development looking at new forms of public value, where i can pursue my desire to rethink the network more overtly.

In that time I’ve led projects around the public service internet and public service data ecosystem projects to exploring elements of the DPS, and we’re still thinking about how to deliver a better internet for our audiences, building on the insights, interfaces and technologies we’ve developed through these projects.

- PSDE: https://www.bbc.co.uk/articles/c70w60975r0o (Hannes_

- Wired: https://www.wired.com/story/bbc-data-personalisation/

- PSI: https://www.bbc.co.uk/rd/projects/public-service-internet

- New Forms of Value: https://www.bbc.co.uk/rd/projects/new-forms-value-bbc-data-economy

And we are far from alone. A lot of people are out there thinking about it talking about it, and credit is due to Mozilla, New_Public, PublicSpaces, and others who are taking the ideas of a sustaining online environment forward in many exciting ways.

- PublicSpaces: https://english.publicspaces.net/

- New_Public: https://newpublic.org/

- Mozilla Foundation: https://www.mozillafoundation.org/en/

- NGI EU: https://ngi.eu/

- Internet Society: https://www.internetsociety.org

And Finally

So, where are we now? I’m with Antonio Gramsci and Tony Benn and two quotes that are often attributed to each of them but which they didn’t actually say (that’s the thing about being a journalist for over four decades – you prefer truth over a good story. See the footnote for the details).

Gramsci’s motto “Pessimism of the intellect, optimism of the will” is embedded in the political armoury of the left as a defining model of how to approach apparently unassailable situations. It has inspired me for many years, along with Tony Benn’s stirring peroration that “There is no final victory, as there is no final defeat. There is just the same battle. To be fought, over and over again. So toughen up, bloody toughen up” remains what I tell myself in the harder times.

Here we are, here I am, fighting the same struggle, objectively pessimistic that we can ever prevail against the bottomless resources and dedication of the new tech empires but unwilling to allow myself to believe that we are destined to lose. The divine right of algorithmic profit-seeking, like the divine right of kings, was made by us and can be unmade by us.

How we do that, whether it looks like the digital public space, or a public service internet, whether we can define a technical approach that allows us to shelter under the umbrella of the dot public domain is less important than the fact that we continue to try, to struggle, to define a way of using these powerful technologies to make the world better and improve people’s lives.

And I haven’t even mentioned AI.

Footnote

Being a journalist means these things matter. Sources count. What really happened is more important than what you would like to have happened.

Gramsci was repeating something Romain Rolland used earlier in a review of The Sacrifice of Abraham by Raymond Lefebvre, but he made It own. And Tony Benn didn’t swear – the speech was actually written by Andy Barrett in the play Tony’s Last Tape, though Benn did say the first bit.

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/08935696.2019.1577616