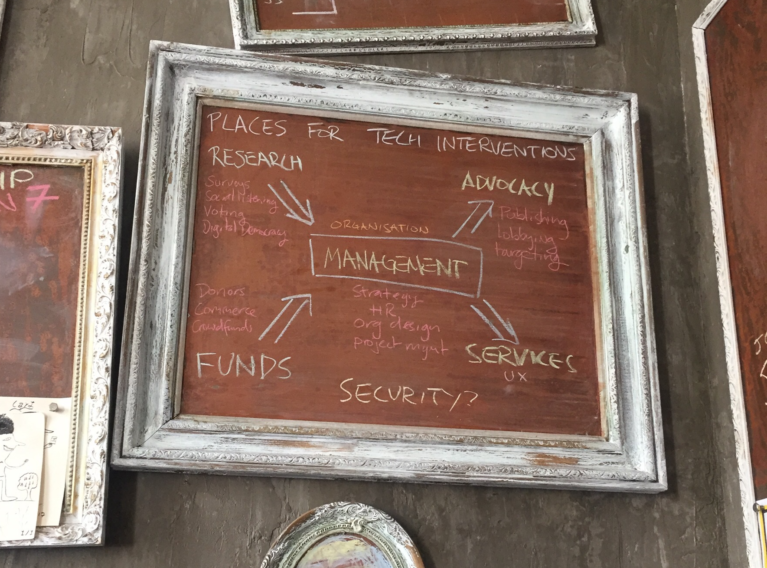

(image: noticeboard at Newspeak House)

We have been anticipating the internet’s impact on the political process for over two decades now, with talk of ‘the first internet election’ going back to at least 1997 in the UK, a time when political parties and candidates built their first websites and started emailing supporters in the hope of influencing their voting.

We have come a long way from the first online MP’s surgery, which I ran for Cambridge MP Anne Campbell in 1996, or the mailing list and website archive that constituted the Nexus ‘online think tank’, and it’s clear that we now have what we asked for: it is impossible to disentangle the political process from the network, and all politics seems to have an online dimension, even in countries where net access is limited.

However the consequences are clearly not those that early advocates of networked politics might have hoped for. Far from the network ushering in a new age of deliberative democracy fuelled by active and engaged citizens, online activism has become a tool for those who would undo the Enlightenment’s gains and push pack many of the social changes that have characterised open societies.

In Brazil, Whatsapp groups helped elect President Bolsonaro, while dark Facebook ads were vital to the Trump campaign in the US and the anti-Europe one in the UK, and Russian troll farms sow confusion and work to undermine the legitimacy of elected politicians and the press around the world. On Buzzfeed News Ryan Broderick gives a long and deeply troubling history of what he calls ‘the dark evolution of internet culture’ and it makes chilling reading.

Twitter, 4chan and Reddit continue to provide platforms for the alt.right, extreme left, and those who simply seek to disrupt and undermine, while populist, nativist, and racist movements around the world have discovered that the internet offers a remarkably welcoming space, bringing people together around shared extremist beliefs and helping them reach and radicalise new converts.

This is not how it was supposed to be when we embarked on the project of connecting the world together and providing tools that would allow anyone to publish what they wanted and reach out to others with ease.

Instead the network has proven ripe for colonisation by those whose worldview is entirely opposed to the early utopians who created this new public space and developed the tools for online engagement. My former optimism – for example here from 2009 when I talked more about this for the BBC – has been comprehensively refuted.

There are many reasons for this. Most significantly. the early designers of the net and its applications, from email to the web, simply did not build in ways to manage online activity because their concern was with fast, reliable communication between network nodes irrespective of their location or the intent of their owners. It was up to the users to manage the contents of those communications – the dumb network simply delivered the packets to willing applications.

The growth of surveillance capitalism as the dominant business model on that dumb network has also been a crucial factor in the emergence of online radicalism and the spread of misinformation, because it’s a model that rewards material which can garner attention, and the shock tactics of those who oppose the liberal worldview are very effective at gaming the algorithms that determine which messages spread.

As things stand, and as John Naughton points out in the Observer ‘network technology makes it much easier for conspiracist ideas to be propagated than was the case in the analogue world of print and broadcast media’.

But does the network inevitably take us to right-wing populism, nativism and autocracy or is it just that the fascists seem to have moved first to exploit the affordances of the net? Are they, like Amazon, exploiting their first mover advantage to consolidate their position as the dominant online voices?

Sadly, it feels to be something more than this. The current online order seems to be attributable to a factor that was first noted back in 1937 with regard to the emergence of authoritarian propaganda in the run up to the Second World War. Simply put, some groups don’t care about telling the truth, and the network rewards those who lie and who don’t care about their lies by giving them attention, influence and – increasingly – political power.

This hard lesson comes from a book called The New Propaganda, written by the socialist and feminist Amber Blanco White and published in 1939. It is a remarkable work, offering a political, social and psychological analysis of the methods being used by Germany’s Nazi government, the Fascists in Italy, and other extremely authoritarian political movements of the time to seize and hold power. [I wrote about it when I first came across it here and you can buy copies second hand if you’d like to read it].

Taking a lead from the then relatively new psychoanalytic theories of Sigmund Freud, White explained the rise of the Fuhrer and Il Duce in terms of father figures and attachment to those who promise safety, particularly from manufactured enemies such as the Communists or the Jews.

She explored at length the use of the most advanced communications technologies of the time, particularly radio and newsreels, to create narratives which encouraged whole countries to feel attacked by outside forces and enemies within, and caused the population to seek salvation in a strong leader who would cleanse the country, secure its borders, and ensure appropriate respect for those – and only those – who were true citizens, united by blood and soil.

The New Propaganda was published by Gollancz’s Left Book Club and distributed to subscribers who could reasonably be assumed to have a particular political perspective, and it is clear on reading it that George Orwell must have taken many of the aspects of IngSoc and the Party structures that underpin Nineteen Eighty-Four from it, not to mention the understanding of the psychological attachments that underpin Big Brother’s power. Newspeak, doublethink, and thoughtcrime are all prefigured.

The methods used are carefully delineated, as White wants to provide assistance to those who would oppose the enemies of freedom and truth and help them take on their opponents in print and over the airwaves, because she was writing at a time when it was still believed that clear factual explanations could counter extremism and that conflict could be avoided.

Writing before the expansionist ambitions of the Nazis had tipped first Europe and then many parts of the world into war, she describes Hitler and the rest of the Nazi leadership as demagogues but not as the monsters history is now compelled to portray them as, and this unusual perspective is helpful at a time when we see many of the same techniques being used by political parties around the world.

The nature of online media is of course radically different from the broadcast and print media of 1937, and social media have massively increased the potential impact on the political sphere and our personal psychology. Where once people might have paddled in the media shallows of newsreels and newspapers we are now fully immersed in the media ecosystem, dependent on our polished stones to act as gateways to an all-consuming online zone of engagement where our psyches, beliefs and attiitudes are shaped.

But this is a good reason to study what happened in the comparatively recent past when media ecologies were simpler, as it may help us understand today’s environment.

And it may help us answer a key question: if these tools are so effective in the hands of the authoritarians, nativists, racists and others who see liberal democracy as an attack on their privilege and power, do they also offer a way for those who feel differently to push back?

The answer is that it seems unlikely. For while liberals, those who oppose authoritarianism, anti-fascists, and even one nation conservatives may be tempted to believe that ‘if it can do it for them, it can do it for us’( a slogan I coined for the Community Computing Network as we attempted to get personal computers into charities and voluntary organisations in the 1980’s), in reality the relation is asymmetric, and it seems unlikely that if they just use Twitter better then they can make the world a better place.

Amber Blanco White makes this clear in the last chapter of her excellent book, where she asks whether the left – including, at the time of her writing, soviet communism of course, – can use the same techniques as the Nazis and the Fascists to achieve their goals, and comes quickly to the conclusion that they cannot.

As she points out, any political settlement that believes in the self-determination of people acting on the basis of rational debate to reduce inequality and deliver social justice must do so on the basis of truth-telling, whether in opposition or government, and such truth-telling is not a viable tactic for the propagandist.

The dictator achieves power by lying, creates discord in society by lying, manufactures enemies and threats through lies, and when caught out will repeat the lie, create a distraction through another lie, or simply exaggerate the lie in order to justify more oppression and more control. The entire political edifice is built on these lies,

These tools are effective because those using them don’t care about lying or being caught out, as there is always another lie behind the current one, a bigger one that will justify whatever steps are being proposed.

Not all lies are equal, of course. At the time the New Propagandists was written politicians in Germany, Italy, and Greece cared about seizing and holding power, while today there are many actors who see benefit in confusion, chaos and the delegitimising of the political structures that define the modern world. For them it does not matter whether their lies are exposed or not – the consequences of being found out are more helpful confusion, not a loss of power and the danger of being overthrown.

But the principle remains: today’s network, and today’s social media tools, are far more effective in the service of liars than truth-tellers.

So what can be done?

One option is regulation, even though that goes against what many perceive to be the spirit of the network. Partly as a result of the US origins of many internet technologies there is often an assumption that free speech is paramount and that the First Amendment must be exported online along with the terms and conditions of sites and services, although of course that is not the case. It’s a view I’ve challenged for many years [see this, from 2002] and I still hold.

It’s not that the net is unregulated, even in the US. There are many regulations already in place and countries from China to Iran to Singapore have put rigid controls in place to protect public order or public morals. In the UK people are prosecuted for online hate speech, and service providers castigated and perhaps even fined for their actions.

But the sort of regulation we need to limit the spead of lies online may be closer to the Chinese model, going beyond setting largely unenforceable rules for commercial services to follow and extending to the creation of online public spaces that are not subject to the pressures that come from having to pay dividends, grow exponentially, or sell attention to advertisers. In a democracy, such an online space would be created to serve the public interest and not that of a ruling party.

It is not impossible to regulate the internet, though it is complex, imperfect and expensive. Passing harsh laws helps, and in China the emerging social credit system will do even more to make people think twice about circumventing the technical barriers.

A better approach might be to work with the grain of society, to offer safe spaces for children, online zones that are nurturing and supportive, and protections from hate speech, misinformation and abuse, and see who chooses them over the chaos of today’s network.

There are precedents. In the UK the emergence of radio transmission as a significant medium for entertainment and potentially information sharing prompted the nationalisation of a nascent broadcasting company, and back in 1926 the British Broadcasting Corporation was created under a Royal Charter, allowing careful control of the means of sound broadcasting in the national interest.

That this interest became a powerful, objective, and socially concerned voice for public good was a result of enormous efforts over the following ninety years by many people, and even today the UK has a tightly regulated broadcasting environment that is widely regarded as a positive force in society.

Other countries took different approaches, most notably the US where the unregulated growth of first radio and then television broadcasting has given us Fox News, Rush Limbaugh and the many evangelical christian stations advocating for Donald Trump.

While I would like to believe that we could build a new internet that could be effectively regulated in the public interest, it may be too late and we may have gone too far for enforceable rules to be the solution. For if the internet were to be rebuilt to make it more easily regulable today then the laws that govern its use would currently be passed by administrations whose interests seem to be served by the current state of affairs and who have shown few qualms about calling for their critics – whether other politicians or unhelpful journalists – to be silenced, and who have themselves spread the lies and confusion that fuel the current political crisis.

It would be foolish to build a new network and bequeath it to those who would only use it to perpetuate oppressive rule and seek to control society in the interests of those currently holding power.

We clearly need to engage politically as well as doing the hard technical work, but another may be to rethink the ways we construct the network itself, to develop tools and technologies that militate against the triumph of falsehood.

In this respect the developments around decentralisation, breaking up monolithic online services and replacing them with open platforms and protocols with real choices of applications and services for people, could make a real difference. A less centralised network with lots of smaller, overlapping communities rather than the massive ad markets of Facebook, YouTube, and Twitter could limit the potential for online radicalisation that the algorithms that drive current online services clearly create [see https://redecentralize.org for more about this].

A decentralised network architecture with a set of regulations that privilege open public discourse might be the best way to move away from the current crisis towards a world where the network can bring people together rather than divide them, where the spread of hatred is controlled and we can nurture an open and inclusive society.

In the end, a network that supports many diverse points of view and limits the potential rewards that come from lying may be our only hope. Because today’s network is no longer clearly a force for good in the world.